In the winter of 2020-2021, five vessels lost nearly 3,000 containers into the stormy Pacific. In just two months, those post-Panamax vessels accounted for more than twice number of lost containers in the previous year. Across widespread media coverage, a kneejerk reaction was to blame supersized vessels or increasingly unpredictable weather. But environmental conditions and vessel design are only part of the picture. Understanding this complex issue, and why losses are incredibly challenging to wholly avoid, holds the key to reducing losses not just from container vessels but across all cargo shipping sectors.

First, some context. According to the Word Shipping Council, international liners transported around 226 million containers in 2019, the last year for which figures are available. From 2008-2019, total container losses averaged 1,382 a year, representing around a thousandth of a percent of containers moved. And until the recent spate, the number of incidents has stayed relatively stable year-on-year, undermining the view that bigger ships and worsening weather are key factors.

Why spend time and resources analyzing such an infrequent occurrence? Because, according to Holger Jefferies, Head of DNV’s Container Ship Excellence Centre, even these few incidences can have a big impact. While the value of goods lost each year is difficult to calculate, there are much more damaging and wide-ranging consequences than the direct financial considerations on ship operators and cargo owners. Rogue containers can put lives, vessels, shoreside infrastructure and the environment at risk.

Every incident has the potential to cause a lot of damage. Then there is a huge cost in finding the containers, cleaning them up, cleaning the beaches where they land and the extra measures that need to be taken when a dangerous cargo is lost.

- Holger Jefferies, Head of DNV’s Container Ship Excellence Centre

Those consequences and clean-up costs typically spread much further than the ship owner, contributing to another reason for addressing the issue: reputational damage. In a consolidated market with just a handful of recognizable companies, maintaining a high safety record is a competitive advantage for container liners. And that perception can be easily negated by images of a broken container washed up on a once pristine beach.

As class rules and IMO regulations seeking to minimize container loss show, there is a motivation to tackle the problem on an industry level.

Design dilemma

Incorrect stowage is one basic factor contributing to container loss. The lashing systems used to hold stacks of containers in place are complex. On a large vessel they can comprise ten thousand of locks, rods and other components that all need to be used in an exact way. If they are not, container stacks can collapse and boxes can be lost overboard.

Lashing systems are designed to consider the weather that container vessels might encounter. The key factors are probability and risk. No ship or lashing system can be designed such that it will not lose containers in any weather scenario. Arne Schulz-Heimbeck, Programme Manager for Containership Development at DNV, draws a parallel with grounding.

“Ships are not usually designed to withstand grounding without damages. Of course, they could be, but it would lead to extremely heavy and expensive ships. The cost of transport would be so high that society worldwide would not accept them.”

It is a similar case with designing container ships and stowage systems for conditions at sea. There will always be outlying conditions so unlikely that to design against them would be prohibitively expensive. In the case of container loss, these conditions are also quite complex. It is not just the environmental conditions that are at play, but the way the ship reacts to them.

As with all modes of transport from space travel to strolling to the shops, a level of risk has to be accepted that cannot be dispelled by design. But just as meteor showers or potholes should be avoided, perhaps simply steering clear of the worst weather and sea states is the best way to minimize container loss?

Route to success

According to Alexander Ozersky, Senior Innovation Manager at Wärtsilä Voyage, routing, as a core element of the puzzle, certainly helps but a much more complex approach is required, rather than simply asking crew to rely on software.

It’s about the properly trained seafarer using the proper solution at the proper time. We break this down into four elements: effective voyage planning, effective real-time warning, detection and analysis of near misses, and effective training.

- Alexander Ozersky, Senior Innovation Manager at Wärtsilä Voyage

Factoring conditions into voyage planning is just the start; these need to be updated regularly, as weather changes, and automated as much as possible so that crew are not overburdened while dealing with heavy sea states. Early warning of dangerous conditions needs to be effective and highly visible – ideally at eye-level where crew will be during rough weather.

Detection and analysis of near misses is an element that is missing from many systems, says Ozersky. That’s why software that can recognize these occurrences is valuable, both in feeding back to algorithms that improve detection, and in helping to inform and educate crew. The findings and new incidences can be factored into simulator training that is essential if crew are to be able to avoid dangerous scenarios and use routing systems effectively.

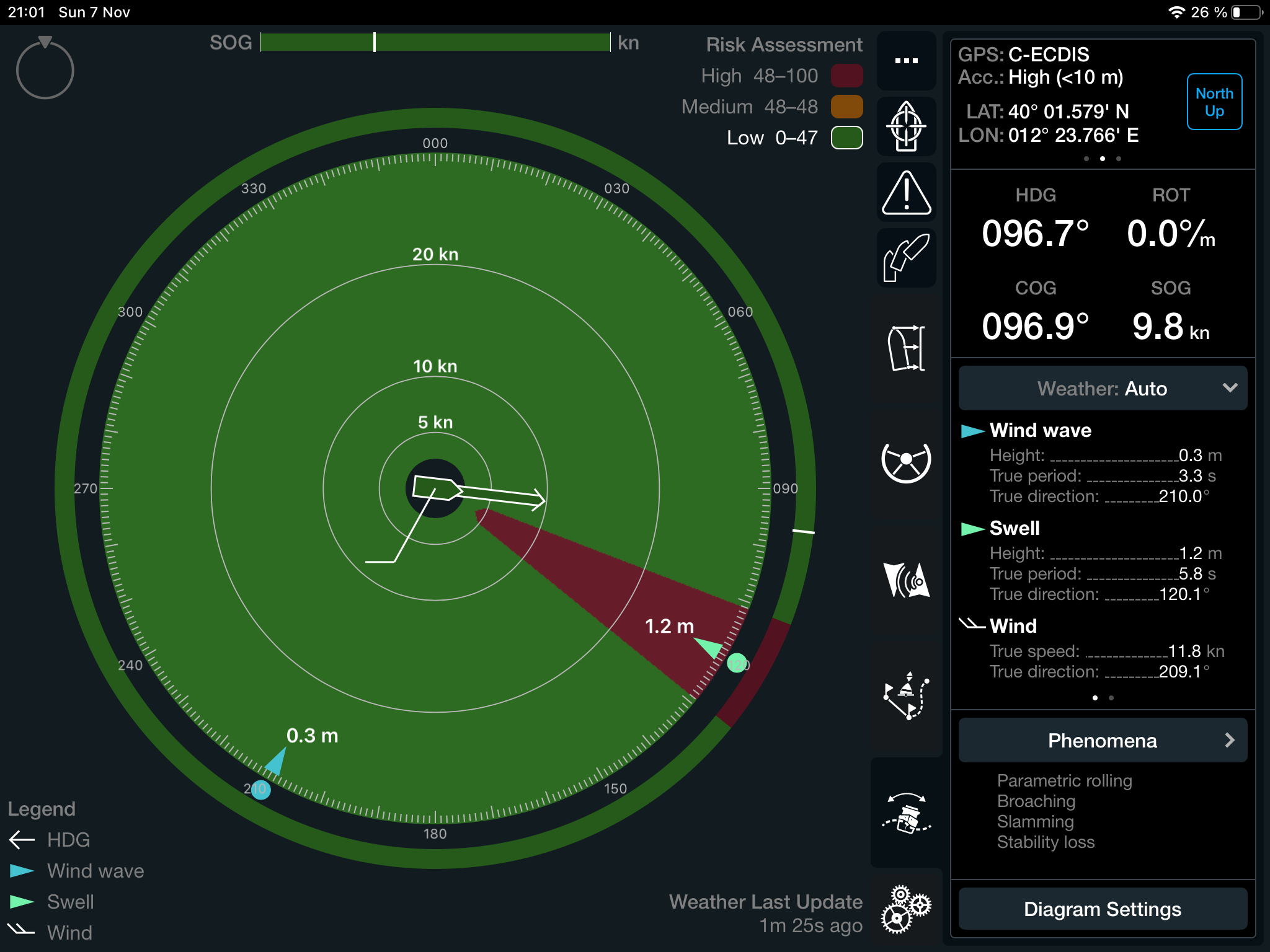

Wärtsilä’s integrated navigation system, Fleet Operations Solution (FOS) deploys voyage planning and weather routing that can help ship crew to steer clear of danger. Its Tracking and Awareness module offers full transparency on navigation, including weather map overlays, live vessel tracking and playback for incident investigation. Moreover, FOS Seakeeping module provides users with the information about comfortable and safe parameters of the vessel's movement (course and speed), which in the given navigation conditions of the voyage will minimise the potential risk of cargo movement and loss. The information is continuously updated, bringing the crew up to speed with the latest data, essential for executing safe and efficient voyages.

However, when it comes to tackling once-in-a-decade incidences of resonance that can put a ship or its cargo in danger, software can only ever be part of the solution.

Future solutions

On an industry level, IMO has included calculations to prevent parametric rolling and other dangerous phenomena in recent updates to its 2008 International Code on Intact Stability. But although helpful for providing general guidance, they do not help crews to avoid specific situations.

“These formulations are fairly rough,” says Schulz-Heimbeck. “If you base a prediction tool on this, for example, it will generate too many false alarms and would likely be ignored.”

If routing software is not the only solution to solve the problem, and IMO calculations cannot serve as a practical guide by themselves, perhaps there is a way of combining these elements? This is something that companies including DNV and Wärtsilä Voyage are working on today. The aim is to deliver routing and voyage planning services that include a better risk profile of situations that could potentially result in cargo loss.

Building this risk profile will be a far more effective way of minimising container losses in the future than redesigning stowage systems. However, cargo loss will remain a complex problem that requires a compound response. Putting responsibility on just one element to reduce losses – be it regulation, training, stowage design or a software – will be unlikely to bring an answer.

Related solutions

Did you like this? Subscribe to Insights updates!

Once every six weeks, you will get the top picks – the latest and the greatest pieces – from this Insights channel by email.