Battery energy storage plays a critical role in stabilising the grid as global energy systems decarbonise

Dennis Voegele, Senior Product Manager, Software Product Management, Wärtsilä Energy Storage

As power grids transition to clean energy, they face a hidden vulnerability: the loss of traditional inertia that kept grid frequencies stable. Synthetic inertia has emerged as a “seatbelt” that can cushion sudden oscillations in supply and demand, preventing blackouts and keeping the lights on.

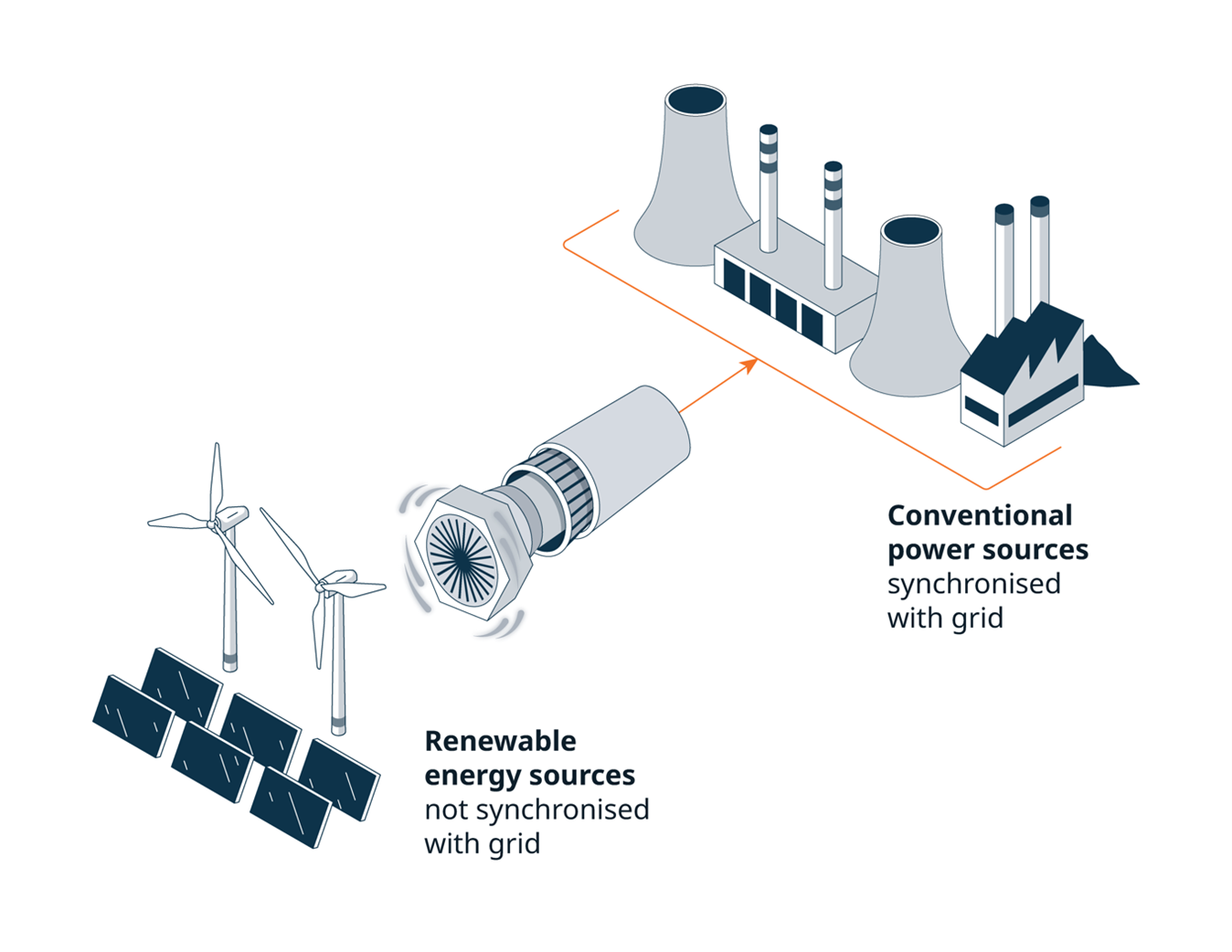

The old guard: how spinning turbines kept the grid stable

For decades, grid stability was implicitly guaranteed by the physics of large power plants. Inside a coal, gas, or nuclear plant, massive turbines and generators rotate in sync with the grid frequency, which is why they are known as synchronous generators. Depending on the grid, this is typically a frequency of 50 or 60 Hz, or 50 or 60 cycles per second. This spinning equipment carries kinetic energy – called mechanical inertia – which refers to an object’s inherent tendency to stay at rest or remain in motion. If a big generator trips offline or a sudden spike in demand hits, the momentum of all those heavy rotors would automatically slow the frequency decline, keeping the grid stable for a few precious seconds. In essence, inertia acts like a car’s locking seatbelt, keeping the passenger safe from abrupt bumps in the road.

Why does this matter? Grid frequency works in delicate precision, balancing supply and demand. If generation briefly falls short of consumption or vice versa, frequency will drop or spike respectively. Inertia provides an instant and critical response. Spinning generators either slow down slightly while their rotational energy injects power to prop up frequency or speed up to absorb the excess.

This buffer gives

grid operators a short window (typically a few seconds) to call upon other

resources before frequency gets too out of balance.

So, what’s changed? This tool worked well for the grid

historically. But, as we shift to an electricity system powered by renewables,

this implicit stability has been in decline. Solar and wind do not have the

same mechanical inertia that’s inherent to turbines of thermal plants.

You’re probably

thinking: don’t wind farms have plenty of turbines? Can’t they fill the gap?

While wind turbines

do spin, modern wind and solar generators interface through power electronics

(inverters) that decouple their motion from grid frequency. Unlike the turbines

we discussed earlier locked at 50-60 Hz with the grid, a wind turbine’s blades

can speed up or slow down with the breeze while converters electronically

produce power. This yields little to no inherent inertia contribution to the

grid (unless equipped with synthetic inertia capabilities themselves). Solar PV

has no moving parts at all, so it contributes no inertia.

When risk becomes reality: the Iberian Peninsula blackout

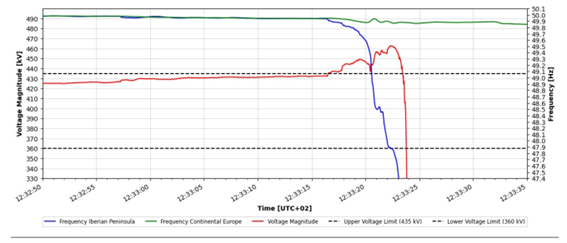

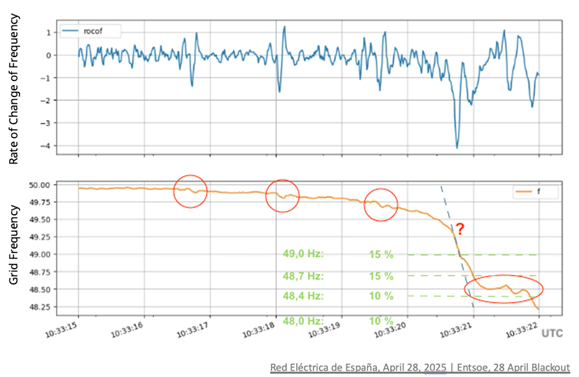

Image caption: The frequency and voltage in Spain and the rest of Europe on the day of the Iberian Peninsula Blackout. Source: ICS Investigation Expert Panel Factual Report, 2025

Grid failures are

incredibly dangerous. It doesn’t only mean the lights go out; outages makes

providing vital services extremely difficult—from keeping hospitals

functioning, streets safe, to maintaining heating and cooling systems that can

mean life or death. They also lead to significant monetary losses as delicate

equipment can be damaged by grid instability. On April 28, 2025, the Iberian

Peninsula experienced a worst-case scenario grid event: the grid went dark for over

55 million people, and it all started within seconds of the first generator

tripping offline.

So, what went wrong? The

grid was missing its seatbelt, meaning, sufficient inertia to maintain

frequency on the grid. This grid failure was a wake-up call for Portugal, which

has since committed 466 million euro to enhance grid management and buffer the renewable-heavy grid with

energy storage.

Fast and flexible: energy storage to the rescue

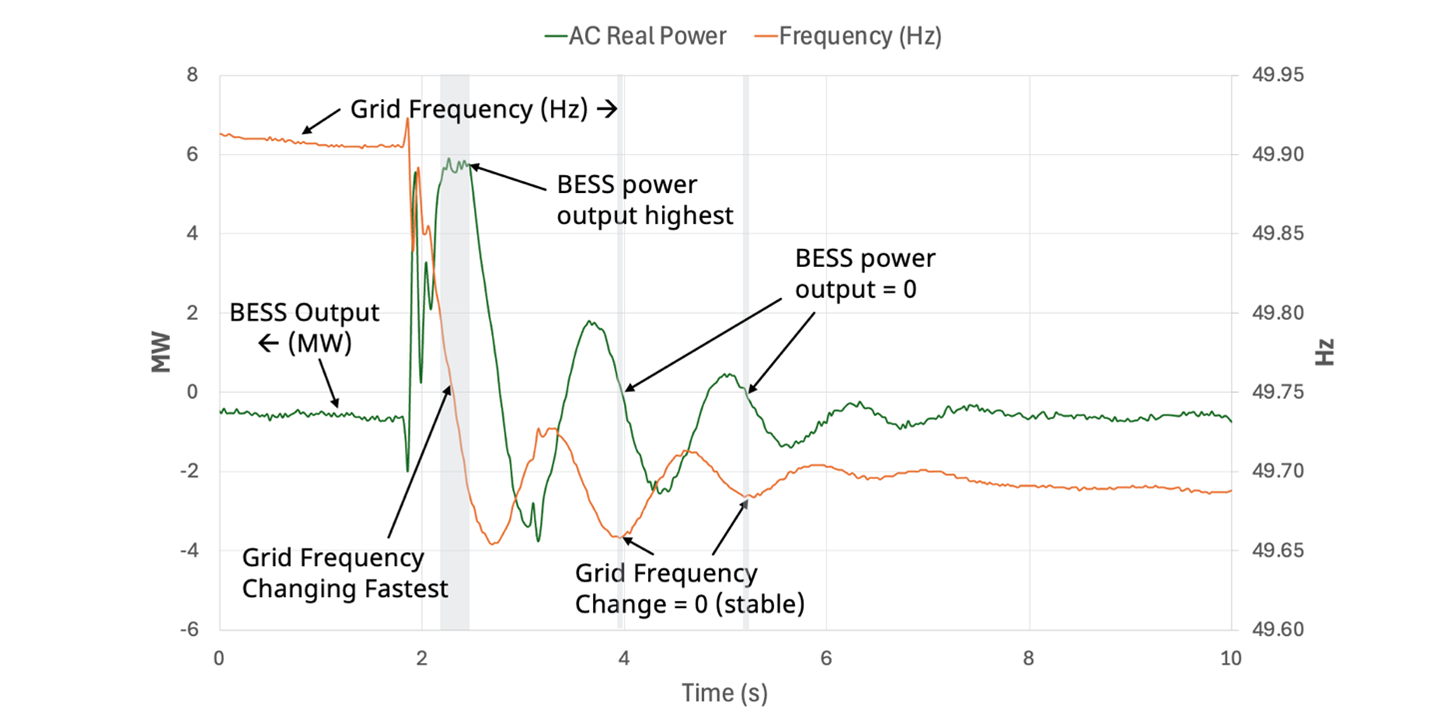

Image: A grid

frequency event where battery energy storage systems (BESS) step in within

milliseconds after a grid frequency event to maintain stability.

On grids with high percentages of renewable

generation, large-scale battery energy storage systems are emerging as the key

enabler of synthetic inertia. Batteries are uniquely suited for this role

because they can both inject power (discharge) or absorb power (charge) almost

instantly on command. This bidirectional capability means a battery can play

the part of a spinning generator’s inertia in either scenario—shortfall or

surplus.

When inertia was abundant, this was a service

that grid operators took for granted. Now, this fast response adds considerable

value to the grid, thereby creating a financial incentive for grid operators to

have more, and battery owners to profit.

In the UK, the

National Grid’s Stability Pathfinder programme is a prime example of this

approach in action. Under this scheme, companies are rewarded for providing

services like synthetic inertia and short-circuit current capabilities, which are

helping keep the system stable as coal plants retire. Zenobē’s system in Blackhillock, Scotland was one of the first of these projects. When it

went live in March 2025, it was the first in the world to offer true synthetic

inertia at that scale to a national grid operator. In doing so, it is helping

replace the inertia once provided by dirtier generation sources, ensuring

renewable power can flow without destabilising the grid.

This approach isn’t

specific to the UK either: Australia is also moving in this direction by

leaning on large-scale batteries and adding grid-forming capabilities in many

new storage projects. The marketplace for fast frequency response in Australia

means battery owners can earn money for stability services that help maintain

the 50 Hz grid frequency. This is a win-win-win: grid operators get the

reliability they need, storage developers are paid for their contribution, and Australians

have a cleaner, yet still reliable, grid.

No time to waste:

safeguarding our grids with BESS

We’ve now seen a major blackout caused by too

little inertia. And, while they don’t make it into the headlines, we’ve also

seen big batteries avert disasters by maintaining the grid frequency.

Around the world, grid operators are waking up to the need for synthetic inertia

as renewable penetration grows, opening a new revenue stream for battery operators.

Looking forward, we expect BESS plants using

grid-forming inverters to become a major contributor to grid stability. By

operating in grid-forming mode, these systems can respond even faster, help

blackstart the grid, and act as backup power for local communities.

As we enter a new era of power, one that is

more capacity strained, decentralised, and dependent on renewable energy,

stability becomes even more critical. Synthetic inertia is the hidden seatbelt

that will make it possible.

Want to learn more?

-

Read Square peg in a round hole: The real issue with

grid stability isn’t renewables in Renewable Energy World by Ruchira

Shah, General Manager Software Management, Wärtsilä Energy Storage.

- See this technology in action: Now operational: Wärtsilä delivers first-of-its-kind energy storage system for Zenobē in Scotland

Did you like this? Subscribe to Insights updates!

Once every six weeks, you will get the top picks – the latest and the greatest pieces – from this Insights channel by email.