It is not electricity alone, heating energy needs to become clean, as well. In an award-winning paper, Wärtsilian Jan Andersson, discusses the feasible bidding strategies under the new Combined Heat and Power (CHP) Act with the German CHP auctions as a case in point.

Electricity prices in Germany have been falling thanks to the growing use of renewable energy sources. To spur the transition towards a more flexible and modern energy system, Germany adopted Electricity Market 2.0 in June 2016. Under this new electricity market system, which is designed to help the country make a smooth transition into renewables, the German Federal Parliament revised regulations under three main categories to reorganise Germany’s power system: the power market law, a capacity reserve decree, and a new law on the digitalisation of the energy transition.

While these are new changes, the Combined Heat and Power (CHP) Act (Kraft-Wärme- Kopplungsanlagen, KWKG) has been in place since 2002 and is another key element in making this energy transition successful. CHP plants generate heat and power simultaneously whilst keeping carbon emissions low. Thus, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy has been incentivising investment in CHP installations with the aim of raising the level of CHP-based power generation.

The Act is quite flexible, and the government has been revising it from time to time to give greater incentives to quicken the adoption of the technology. The latest amendments came in 2017 when the government decided to have an auction for innovative CHP systems. According to the ministry’s website, “This new category of funding is intended to open up promising new prospects for combined heat and power and to provide incentives for necessary investment in flexible technologies.”

This offers great possibilities for German utilities, since an auction serves as a driver to enhance innovation and flexibility in CHP production.

Jan Andersson, Market Development Analyst, Energy Solutions, at Wärtsilä, has studied the CHP auction scheme closely. In his paper ‘Flexibility is the New Black – How Flexibility Enhances Value in CHP Portfolios’, Andersson analyses three bidding strategies and explains how innovative and flexible technology adds value for utilities in this new market landscape. His work was awarded the Best Paper at Electrify Europe 2018 (formerly known as PowerGen Europe).

Here are the highlights of his paper:

Uncertain CHP Auctions

When the subsidy rates for traditional CHP plants of 1 MW up to 50 MW was auctioned for the first time in Germany, on 1 December 2017, a pall of uncertainty descended upon the participants before the auction. What results could be achieved through an auction? Which bidding strategy would be successful? And how could the overall profitability of CHP projects be presented under these framework conditions? These were some of the many questions they worried about.

The capacity of the first auction was 100 MW. With subsidy rates of up to EUR 70 /MWh, participation in the auction was attractive for many companies.

Finally, the first auction was cleared at the range of EUR 32–50 /MWh for a total of 83 MW.

Ever since, there has been an increasing interest among the participants to bid into the upcoming auctions. This is an interest that is also partly fuelled by the fear that the CHP subsidies could be discontinued in the future, and thus any investment needed for replacement or extension should be undertaken as soon as possible and under the regulations of the current CHP Act.

The current KWKG Act aims to increase the co-generated power generation to 110 TWh in 2020 and to 120 TWh by 2025. The central instrument here is the auctioning of KWKG subsidies for the generation of CHP electricity.

Everything but coal

Participation in the tender is compulsory for all new and modernised CHP plants with an electric CHP capacity between 1 MW and 50 MW. However, a transitional provision stipulates that facilities that were ordered in 2016 or have been granted a permit in accordance with the Federal Immission Control Act (BImSchG) and will be put into operation in 2018, are eligible to participate in the tender procedure.

The promotion of CHP power generation is basically possible for all fuels except coal. This means that CHP plants, for example, based on biomass (solid, liquid, gaseous), waste-based plants, as well as gas-based CHP plants, are eligible to participate in the auction.

The auction distinguishes between traditional CHP and innovative CHP schemes. The auction held in December 2017 only considered traditional CHP, whereas, the auction in June 2018 also included innovative CHP schemes.

Traditional versus innovative

Let’s start with the traditional CHP scheme. This focuses on the CHP performance of fuel-fired plants, which is similar to the guaranteed CHP scheme for plants larger than 50 MW. No additional technological specifications are made for this scheme. The legal framework provides for a maximum CHP bonus of EUR 70 /MWh to traditional CHP plants. In addition, subsidies for conventional CHP plants are limited to a total of 30,000 full-load hours. Also, twice a year, 75 MW of KWKG subsidy is auctioned under the traditional CHP scheme.

The innovative scheme, on the other hand, includes CHP plants that are combined with renewable heat generation technologies and additional power-to-heat technology. Meaning, CHP plants that combine heat pumps, solar thermal or geothermal energy. Here, the share of renewable heat must amount to at least 30 % of the annual total heat production from the plant.

For innovative CHP systems, the maximum subsidy rate is EUR 120 /MWh and this subsidy is limited to 45,000 full-load hours. 25 MW of KWKG subsidies is auctioned twice a year under the innovative CHP scheme.

In addition, there is also an annual limit for the subsidised amounts of energy. To encourage more flexible plant operation, the subsidy is paid for a maximum of 3,500 full-load hours, per year. Only the first 3,500 full-load hours of a year are eligible for a subsidy.

Herein lies an optimisation challenge: the plant should run only for 3,500 hours during the year with the highest electricity prices. However, it does not mean that the plant cannot be operated after reaching this annual limit of full-load hours. It only means that these excess operating hours will not be eligible for a subsidy.

Select the right strategy

This is where choosing the right strategy comes into play.

Before bidding on the auction, a bidding strategy should be worked out. The art of an auction strategy lies in finding a bid level for the project that accurately reflects the return versus risk appetite. However, this should not be a decision based on gut feeling. Instead, it should be anchored on a sound analysis of the energy market.

There are no simple strategy recommendations. An individual strategy development that includes the following three factors, is necessary:

1. Successfulness: It is necessary to realise that the project plays an important role, that is, there is a need to replace an existing CHP plant or increase capacity in order to maintain the heat supply of customers.

2. Risk appetite: The risk preference differs from bidder-to-bidder and from project-to-project. Certain companies will be prepared to accept a lower probability of success if the expected return is favourable, while others may not.

3. Competition: Not only the costs of your own project are relevant, but also the costs and bid strategies of the competitors. This requires an analysis of which projects might be included in the auction round and at what cost. Once an assessment of the above-mentioned topics has been done, a promising bid strategy can be defined based on an optimised bid mark-up and the probability of winning.

The math behind the bid

In a ‘pay-as-bid’ auction, every successful bid receives the amount with which it went to the auction. Therefore, the optimal bid is the one that is as close as possible to the last bid still to be cleared. Thus, unlike the pay-as-cleared method, pay-as-bid auctions require strategic bidding behaviour.

However, since no bidder knows the marginal price at the time of participation, there is an inevitable trade-off: the higher the bid, the lower the probability of winning but better profitability in the event of a successful bid.

Methodologically, in the past pay-as-bid auctions, it has helped if the bidding strategy was determined in two steps. First, determine the minimum bid, or, the so-called indifference price. Second, determine whether it makes sense to bid above the indifference price, also referred to as the strategic bid mark-up.

The indifference price is the bid price at which the bidder does not care whether he or she wins the bid or not. The basis for determining the indifference price is formed by accurate estimates of cost, revenue, and risk structure of the project. Auctions mean competition and any competitive advantage can be converted into a higher probability of winning or obtaining better project returns. Therefore, accuracy is very important here.

One of the main aspects of setting the indifference price is costs, especially investment costs. Investment costs can be determined relatively accurately, however, the critical point here is to consider the full scope of the project. The second part is determining a risk-adjusted minimum return for the project. It is often seen that most internal discussions are around this topic as the operation of a CHP plant is not a risk-free business. Even if the CHP subsidy is safe, technical risks and, of course, the electricity-price risk remains.

Hence, the next natural step is to make an estimate of future market developments: electricity price, gas price, heat revenue and other variable factors.

It is important to make the decision-making process and calculations to arrive at the indifference price, as objective as possible. It is also important to keep in mind the internal interests of the company and, if necessary, include a third-party perspective. If all the above points are taken into account carefully, the result is a neutral indifference price.

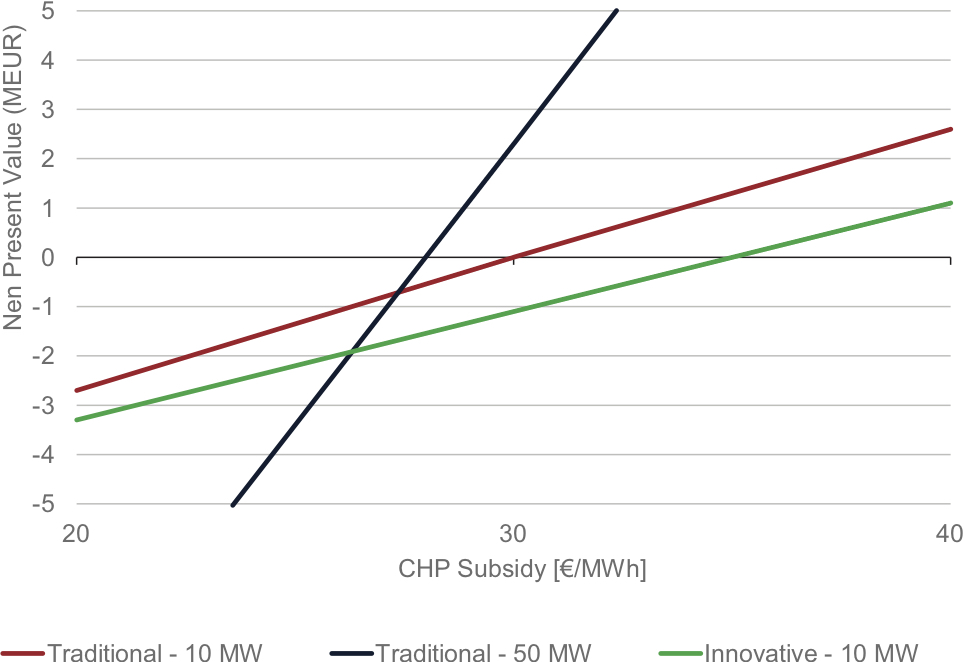

Figure 6. CHP subsidy versus net present value.

Lessons learned

What is the overall picture of the profitability of the plants? Figure 6 (above) shows the determined break-even CHP subsidies of the plants. The point where the lines intersect the X-axis, is the "break-even CHP subsidy rate".

Overall, the level of subsidy rates required is low. The plants considered here, larger gas engine power plants, can hence be very competitive in the auction.

The level of subsidy required for traditional plants is in the range of EUR 25 to 30 /MWh. The bigger plants tend to have lower break-even rates, that is, they have a lower need for subsidies. This is due to the lower specific investment and operating costs of the plants.

For the innovative scheme, the break-even value lies at approximately EUR 35 /MWh, which is less than what could be anticipated considering the small size of the plant and the additional capital cost of solar collectors and heat pump. However, the longer eligibility period of 45,000 full-load hours is one obvious explanation. In addition, a couple of conclusions can be made based on the result.

One, the inclusion of renewable heat generation equipment gives more flexibility even to the heat generation side. This gives the opportunity to optimise heat generation irrespectively of electricity production.

Two, despite the positive effects of renewable heat generation assets, the related investment cost still outweighs the benefits. However, decreasing investment costs and increasing emission costs could change this rapidly.

Going Forward

The first auction held in December 2017 cleared in the range of 32 to 50 EUR/MWh with two plants greater than 30 MW capacity. After analysing the results of the December auction, it is clear that the above method picked the low-end of the subsidy rate and tends to favour larger projects over smaller ones. The higher end of the interval is clearly below the maximum of EUR 70 /MWh, which is also an indication that the bidders did more than speculative bidding.

Since KWKG does not include any fuel switch premiums for coal replacement projects in the auction segment, the economic effects of this additional remuneration were not taken into consideration. However, it is apparent in the market that many projects are attempting to project larger systems (greater than 50 MW) and thus obtain the fuel switch premium outside of the auction segment.

The heating sector is often overlooked when discussing emissions and reduction targets. The fact is that the generation of heat in Germany accounts for roughly the same amount of CO2 emissions as electricity generation. Therefore, the initiative to include renewable heat generation as a special segment in the KWKG shows the will of the German government to reduce emissions in the heating sector as well. Even though renewable heat generation technology still requires higher investments, it is pointing towards a new, more environmentally friendly future for CHP.

Did you like this? Subscribe to Insights updates!

Once every six weeks, you will get the top picks – the latest and the greatest pieces – from this Insights channel by email.