There are some things that never change in California – the satin sheen of Hollywood, the sun-bleached tousle of young surfers, the interpretation of tremors along the fault-lines. Though these are known dreams and dangers, there’s something few people know about this state: per capita, electricity usage has barely changed since the mid-1970s.

Not all of us even remember that far back. In 1975, Barry Manilow’s single Mandy went gold. Lennon was still alive; Navratilova still played tennis. And it was the year of the oil crisis in the US when people had to queue to buy petrol (or stand in line, as the Americans themselves would say, to get gas).

One of those people was Arthur Rosenfeld, an experimental physicist, who would soon set aside his study of subatomic particles to help design energy-efficiency standards and technologies. And a man who can take credit for the stalled per capita consumption of energy, while the rest of the US has nearly doubled its per-capita electricity consumption since.

Genesis of efficiency standards

It was during the oil crisis, when about to go home via the gas-pump line, that Rosenfeld turned off his office lights and wondered how much energy they could save if everyone had an austerity-minded attitude towards electricity use. The Washington Post writes that Rosenfeld went on to take a simple tour of his office, tallying lights and appliances, and realised his office alone could save the equivalent of 100 gallons of petrol per weekend.

A few years later, Rosenfeld had a meeting with the state governor, and the first steps were taken towards energy-efficiency regulation on refrigerators. Anyone who has a modest and not-so-updated country cabin will recognise the type – that kind of heavy, unyielding box looming large in the kitchen, consuming so much electricity that it emits a grizzly-like growl and a dolorous clank when it kicks up a notch on sweaty afternoons. After Rosenfeld’s meeting with the governors, such fridges could no longer be sold.

New fridges also had to be designed to the new standards, which had national ramifications, as Rosenfeld’s former student and long-time colleague Professor Ashok Gadgil explains. "It didn’t make sense to have two production lines. Manufacturers said, ‘Damn it, it’s not worth it. We’ll just make one production line.’ So, California led the way and caused refrigerators for the entire country to be made to California standards,” Gadgil tells Twentyfour7.

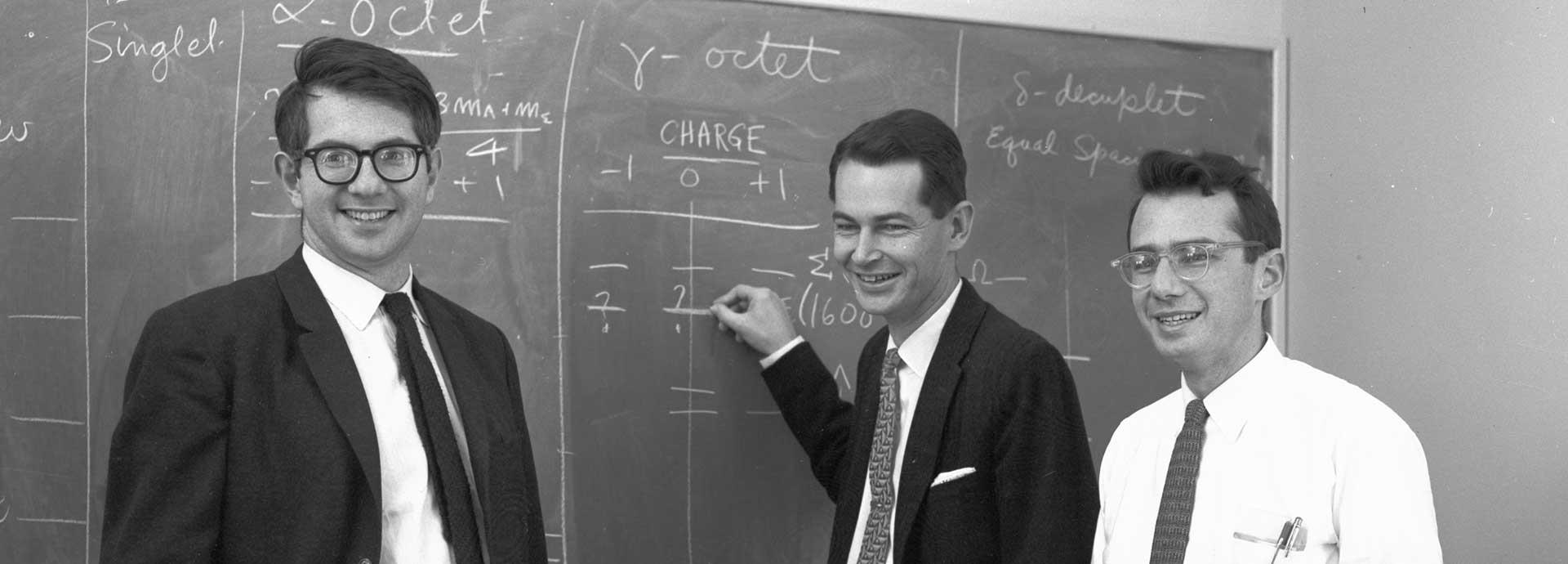

Arthur Rosenfeld (R) with his colleagues Sheldon Glashow (L) and George Kalbfleisch (M) demonstrates the new evidence for the "eight-fold way theory of strong interaction." Blackboard notation shows how newly discovered particle, Y*-1, fits into an unfilled octet of the "eight-fold way," taken January 4, 1963. Morgue 1963-1 (P-5)

Towards the common good

Apart from new technology, the cooperation with legislators for what people call the common good was new – and not without controversy in free-market America – argues Gadgil. Research showed that the shelf-price of a household appliance meant more to the buyer than how much they’d pay for the electricity to run it. So legislators had to go in to make a change. "Rather than just wringing his hands and thinking it’s terrible that consumers only think short-term, Rosenfeld thought about how society could solve this problem. Then he worked with legislations to do something that markets alone can’t do because of individual behaviour,” he says. "That was a bit counter to the free-market tendency of American economists then, and it is still against that tendency.”

The idea was never to antagonise manufacturers, which legislators kept in mind when phasing in new regulations. "The rules were announced three years in advance so producers had enough time to thicken their insulation so there was not a catastrophic emergency,” Gadgil says, but adds that manufacturers did take the matter to court. The key then was for the scientists to stand their ground with cool heads and account for the calculations and data. "The methodology is transparent. It was legally challenged by the Association of Manufacturers, and it had to be fought and proven to the judges that these regulations were indeed substantially in favour of societal interest,” Gadgil says. "This had to be rigorously done and was not just an idea.”

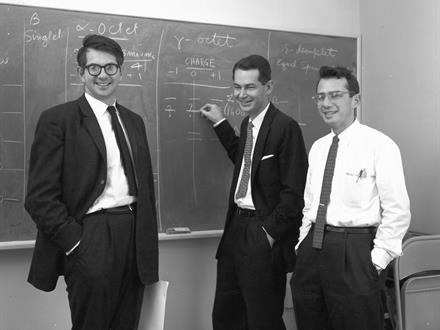

Meeting reporters after the announcement of the Omega meson discovery are Lynn Stevenson, Bogdan Maglic, Luis Alvarez, and Arthur Rosenfeld. Morgue1961-17(P-17)

It’s all about the savings

Fridges were just the beginning, and many more steps followed. A team of researchers at Berkeley’s Center for Building Science, led by Arthur Rosenfeld, helped develop electronic ballasts, which would make the compact fluorescent lamp possible and popular. They developed a coating for windows to trap heat in the winter and keep it out in the summer, and insulated homes further with a reflective roof design that aids with cooling.

And, long before data was the hottest name on the block, they developed computer programs to analyse how much energy buildings used. A year after the fridge rules came into effect, the state governor also updated the building codes in an attempt to cut energy waste. And these rules were successively tightened on a cycle of about every three years.

Such were his efforts and achievements that Rosenfeld would become synonymous with energy efficiency, and his name was given to a new unit, the Rosenfeld – a savings of 3 billion kilowatt-hours per year. To put that in proportion, it’s the same electrical energy that a 500-megawatt coal-fired power plant can generate in a year.

Paragon of open-minded curiosity

Yet, he remained a modest man, says Gadgil, who remembers Rosenfeld fondly. "He was wonderfully generous without a big ego, which is unusual among professors, particularly for someone who saved the United States 500 billion dollars just on appliance standards. His future savings to the US economy will be another half a trillion dollars,” Gadgil points out.

Rosenfeld kept active on campus – and as a Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Distinguished Scientist Emeritus – often dropping in on seminars. "He’d love to sit in the front row and ask tough questions. But the seminars were usually in the afternoon, and if Rosenfeld started dozing in a seminar, it was a good sign. It meant that he was sure that the work was good quality, and he could doze. If he wasn’t dozing, that meant he was likely irritated and sharp and would be soon asking tough questions,” Gadgil recalls. "Most people think that, if the listener is dozing, he is bored, and it’s not a good seminar. With Rosenfeld, it was the opposite.”

At the time of his death in early 2017, Rosenfeld had grown frail but had lost none of his wit. Gadgil says of his friend that a childhood spent abroad made him open-minded and curious, and success hadn’t dampened either nor his generosity. "Despite those successes, he had an easy smile and was very approachable. Maybe because of his childhood experiences abroad, he always was very open and friendly to people from other countries.”

Did you like this? Subscribe to Insights updates!

Once every six weeks, you will get the top picks – the latest and the greatest pieces – from this Insights channel by email.